|

| Cigar-shaped UFO |

Witnesses at the time said the spaceship exploded upon impact with the windmill and the largest piece of debris hit a large tree with smaller pieces scattered across several acres. In the debris was found pieces of strange metal inscribed with hieroglyphics and the body of the pilot, a small child-sized humanoid. Although the body was badly torn up, it was evident it was a being "not of this world."

|

| Entrance of Aurora Cemetery |

On April 19th, a small article appeared on page 5 in the Dallas Morning News. It read:

"About 6 o'clock this morning the early risers of Aurora were astonished at the sudden appearance of the airship which has been sailing around the country. It was traveling due north and much nearer the earth than before.

"Evidently some of the machinery was out-of-order, for it was making a speed of only ten or twelve miles an hour, and gradually settling toward the earth. It sailed over the public square and when it reached the north part of town it collided with the tower of Judge Proctor's windmill and went into pieces with a terrific explosion, scattering debris over several acres of ground, wrecking the windmill and water tank and destroying the judge's flower garden.

"The pilot of the ship is supposed to have been the only one aboard and, while his remains were badly disfigured, enough of the original has been picked up to show that he was not an inhabitant of this world."

|

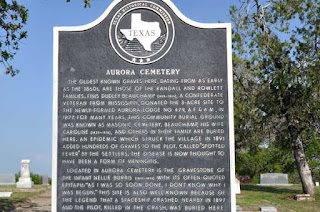

| Texas State Historical Marker at the Aurora Cemetery |

|

| Alien grave? |

When I visited recently, I found the residents living across the street from the cemetery to still be wary, watchful, and protective. Parking by the front gate, several dogs began barking as soon as I exited my truck and an elderly lady came out onto her porch to watch me. I waved to her and I think she nodded in return, but I was far enough away that I couldn't be sure. She watched me for a few minutes and then went inside her house and opened the curtains in a front window. About 10 minutes later, a police car slowly cruised by, but didn't stop. I was dressed in good jeans and a pullover shirt and carried nothing in my hands except my camera so I guess I passed his inspection.

|

| Alien's headstone? |

I had been roaming around the cemetery for about an hour and nobody else came in. There had even been very few cars pass on the road, but I still felt like I was being watched the whole time. I'm sure the old lady across the street never took her eyes off me. It wasn't a scary feeling, it wasn't like that "somethings not right, I better be on alert" feeling you sometimes get when you are by yourself in an unfamiliar place; just that general feeling of having someone's eyes on you. I noticed the police car slowly cruise by again, but by then, I was already on my way out. I waved at the policeman and received a small wave of his hand in return, but no smile. I could almost hear the thoughts in his head saying, "It doesn't appear you are here with harmful intent and you are not breaking any laws, but I'm keeping my eye on you just the same." I didn't hang around to see him come back a third time.

I don't know if there's anything in the "alien" grave or not; don't know if the tale is true or not, but either way, it's an interesting story.